They’re rampant.

Or not.

A while ago, I posted a link to Xenos Rampant, a fan-mod of the tabletop miniature wargame Dragon Rampant. About a year ago, I decided to email the author, Daniel Mersey, and see if he minded if I submitted it for proper publication as a standalone game.

Well, the upshot of it is that Xenos Rampant is no more.

These days, it’s just Xenos, and I’m now a co-author.

The game’s still in the play-testing stage, with a long way to go, but I’m quite liking how it’s going.

Without going into specifics (not least because anything’s subject to change before the final product), the Dragon Rampant rules have been tweaked to make them fit a style of skirmish warfare more suited to science fiction than the medieval fantasy of the original. Specifically, I’m looking to shape something that replicates the broad strokes of firefights from the early twentieth century to the present day and into the hypothetical beyond.

The morale rules are being revisited, as are the shooting rules, and there are, of course, rules for vehicles. What we’re not going to do is go BIG. You know, with tank companies clashing with thirty-metre high bipedal war machines armed with enough firepower to level a city. This is platoon-level stuff, with roughly half a dozen units per side and only a limited number of vehicles.

The game’s setting-neutral, so you can use any appropriate models you like, with generic unit types that can be customised to represent virtually any science fiction setting through the addition of special abilities and upgrades. There aren’t any firm army lists, not even ones in the fantasy trope style of Dragon Rampant. Instead, there are sample armies to demonstrate how to compose an interesting force using the generic Xenos army list.

To simplify things, I’ve split that section of the game up into a couple of genres. This, conveniently, helps me organise my own hobby plans for the next couple of years, as I want to put a couple of forces together for each genre, not least for playtesting purposes. Handily, several of these genres lend themselves quite nicely to non-science-fiction games as well. Almost like I planned it.

Operation Werwolf – Weird War Two: The closest to a specific setting that Xenos gets, this is the style of occult fantasy-horror that you know from films like Indiana Jones, Overlord or video games like the Wolfenstein series. The idea is that the historical Werwolf organisation was subsumed in the latter stages of the war by two factions of Nazi occultists – the sorcerous Schülers and the xeno-technologist Handwerkers. On the other side are British magicians of the Strange Research Group, the US Operation Paperclip (where do you think the flying saucers at Roswell came from?), and the Soviet Union’s… basic rank and file soldiers because no good communist believes in the supernatural. I’ve already painted up a platoon of Soviets and am halfway through a Schüler force.

The Meanest Streets – Urban Fantasy: Modern-day cops and cultists, basically. I’ve come up with separate sample detachments for British and American style police, as well as urban and rural cults (think gangbangers and militias, with added demons/aliens/undead). Think the ‘secret war’ style of science fiction, as seen in The X-Files, Fringe, Threshold and the like, but when things have escalated to all-out shooting. Alternatively, this genre could cover the day-to-day ultraviolence of Robocop and other cyberpunk pieces. My armies for this genre are going to be a well-funded and well-armed occult research organisation, a pack of feral, desert-dwelling ghouls, and a US militia group that fell into the worship of something they found in the woods of the Pacific Northwest.

The War on Terra – Five Minutes Into The Future: Another modern day genre, but focusing more on the military response to overt alien invasion than the secret wars of The Meanest Streets. Various types of modern military forces are covered, from professional Western-style forces through PMC’s, conscripts, warlord militias and insurgent groups, which can be fielded against each other (or forces from The Meanest Streets, I guess), but are meant to be pitched against a couple of lists for alien invaders and their human collaborators. Influences for this sprawling genre are too numerous to list in full, but The War of the Worlds is an obvious one, as are numerous modern war films. I’ve already painted up an extremely small army of US special forces operators (24 points for twelve models), and intend to add an army of alien collaborators.

After The End – Post-Apocalypse: Inspired by Metro 2033, Mad Max, Fallout or a million zombie apocalypses, the sample armies cover several types of survivors, barbarians, bandits and road warriors, as well as a zombie horde and, as a beacon of hope in a dying world, an actual, honest-to-God angel and her followers. Or maybe she’s just a mutant and they’re murderous zealots. It’ll be a while before I get around to painting these guys, but Metro-style nuclear winter Muscovites are tempting (I have some bits left over from my Weird War Soviets, which is handy), as are the angel’s disciples, and the road warriors and their custom cars, and then there’s always the zombies…

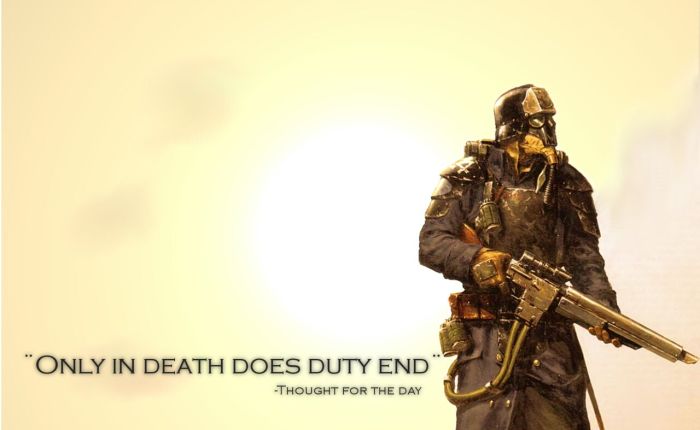

Beyond The Final Frontier – Space Opera: If you were wondering where the ‘proper’ science fiction was in Xenos, it’s here, available in all shades from shiny to grimdark. Sample armies include landing parties (some of whom wear red shirts), the storm troopers of the evil empire, boarding parties, space pirates, xenomorph swarms, primitive pulp-style barbarians, artefacts left behind by the Ancients, artificial humans (“The masters created us, gave us intelligence, but then they… left.”), super-soldiers and pan-dimensional demonic horrors. Even more so than After The End, I’m spoiled for choice, but I’ve already painted up a force of near-future UN peacekeepers (as seen in the header image), and have plans for steampunk neo-Victorians in pith helmets, plus some Firefly Reaver-style pirates and a heavily-armoured space dwarf boarding party painted in the same colours as my Dragon Rampant Chaos dwarves.

I’m going to post more images and write-ups of my armies as I finish them off. Currently, the only ones finished are the Weird War Soviets, the War on Terra special forces team and the Space Opera UN peacekeepers. Although, as we all know, no wargaming army is ever ‘complete’. There’s always another cool set of models to add. When you’re a grown-up with a full-time job, collecting models is as much about restraining yourself as it is splashing out your disposable income.

Anyway, back to compiling playtest suggestions.